Fragmented landscape creates opportunities in emerging market bonds

Emerging markets are facing a tough economic environment but some countries are performing better than others, creating opportunities for investors

Emerging market (EM) debt has grabbed the headlines recently, first by the US Supreme Court’s ruling on Argentina’s $95bn (€71bn) default and then by its referral to the International Court of Justice. At the time of going to press, banks including Citigroup are attempting to put together a group of buyers for the disputed debt which could resolve the US lawsuit that is blocking Argentina from servicing its foreign bonds.

These developments are important, not just because of contagion – in fact Argentina represents just 1.9 per cent of global bond markets – but because virtually every emerging market country has experienced debt problems. This is Argentina’s eighth default since 1826, which is the same incidence as Peru, Mexico and Turkey and less than Brazil, Chile, Ecuador, Venezuela and Costa Rica.

Critically, these developments are helping the IMF push through a proposal making it easier for governments to force bondholders to accept restructuring terms, which would in future deter investors from buying higher risk sovereigns. The IMF plans to refuse help to countries with unsustainable debt burdens, unless creditors first agree to a debt restructuring, so helping prevent the Fund from repeatedly throwing good money after bad.

Despite these concerns, EM Bond indices are up around 8.5 per cent this year. This is a remarkable feat as most emerging economies have been struggling with stagnant growth and heightened volatility in FX rates and capital flows, as well as elections and geopolitical events, which typically raise risk premiums. Meanwhile, growth is improving across their rival developed nations and central banks remain accommodative.

Valuations have bounced back from their low levels last year when EM debt was as cheap as at any time since the 1998-99 Russia and Asia crises. The yield advantage over Treasuries is now around 2.5 per cent, only 50 basis points above the record low, and the sector has outperformed developed market high yield by about 2.6 per cent over the year to date.

“There have been significant returns in investment grade external sovereign bonds this year which, having suffered disproportionately in the sell-off in 2013, have rebounded, supported by the compression in US Treasury yields,” says Amanda La Marca, senior product specialist at HSBC. “More recently, high yield names have performed because of the stable rates environment and accommodative monetary policies from developed markets,” she says.

On the local side, much of the performance is driven by currencies that ended 2013 undervalued and have rebounded year to date.

The asset class is now stretched with limited potential for capital gain, she believes. “Over 70 per cent of the hard currency sovereign universe is investment grade rated according to the JP Morgan EMBIG Index, so there is a high sensitivity to movements in Treasuries. Negative performance could in future be triggered by the Fed – rising rates will have a large impact on emerging market fixed income assets and will also make it less supportive for capital flows into EM countries.” This would weaken local currencies and make it more expensive for these nations to service their debt, adds Ms La Marca.

“The bad news is that the next five years won’t be anything like the last five,” says Jack Deino, head of emerging markets fixed income at Invesco. “Last year, investors chased too few assets so there was a lot of heavy positioning from guys who perhaps should not have been there, and a complacency about volatility. Now the position has cleaned up and much of the fast money is out of these markets.”

The bad news is that the next five years won’t be anything like the last five

Two factors have been very beneficial, he explains. One is liquidity. “Despite potential easing by the ECB, the Fed, which has been the 1000 tonne gorilla in the room, is slowly moving to a tightening bias in comparison with very loose monetary policy that has benefited EM assets over the past few years,” he says. Likewise, the ‘supercycle’ in commodity prices is unlikely to be repeated.

However, the market is becoming more geographically fragmented, presenting idiosyncratic opportunities. “Although EM spreads have shifted significantly tighter since February, the move has not been in unison on a regional basis,” says Jon Brager, senior credit analyst at Hermes.

Latin American corporate credit initiated the rally and spreads have essentially moved one-way tighter since, he explains. Emea significantly underperformed as the crisis in Ukraine intensified – but spreads have recovered. Asian spreads have moved tighter only recently, as concerns over Chinese growth appear to have ebbed in recent weeks. Overall, EM high yield spreads are more than 100 basis points tighter year-to-date, compared to about 10 basis points for developed markets. The ratio of EM to DM spreads has compressed to 1.57 – from 1.63 at the start of the year and 1.84 in late February, adds Mr Brager.

“The spread ratio between EM and DM has historically averaged around 1.2, outside of crisis periods,” he notes. “While we do not expect a return to this ‘normal’ level, given the less favourable macro outlook and uncertainty regarding Fed policy, we do think there is scope for further relative tightening to the 1.3-1.4 area.”

This optimism is based on three themes. Firstly, global demand for yield remains strong, and developed market products are not filling that gap. Secondly, many EM issuers are global enterprises, with geographically diversified exposures, that have been unfairly punished for their domicile. Thirdly, many EM credits have the capacity to improve their credit profiles despite the macro backdrop because the poor operating environment has made them refrain from risky acquisitions and excessive Capex.

Simon Lue-Fong, head of global emerging debt at Pictet Asset Management, who was caught out when the Fed delayed the taper last September, also predicts a better second half with EM economies and currencies starting to make progress. “I think we may see a V-shaped return pattern this year,” he says, “with good growth in Columbia, Brazil, Philippines and Poland.”

Interest rate cuts spur could spur growth, believes Mr Lue-Fong. “Exports have collapsed since 2011,” he says. “Where there is tepid growth, one lever is always to cut domestic internal rates. However if their currencies weaken significantly, then that could stop them as they need a stable currency. It also depends on what the Fed does. If the Fed tightens, then it would be hard for other central banks to cut rates.”

If growth is pressurised, that helps central banks to think about tools, he says. Mexico and Turkey cut rates recently so the process is beginning to happen.

Others point to a real improvement in fundamentals brought about by switching from fixed to floating currencies. Edwin Gutierrez, senior investment manager at Aberdeen Asset Management, points out that India and Indonesia have been reducing their deficits effectively. In India the current account deficit was 4.5 per cent at its peak but has dropped to 1.5 per cent. In Indonesia, it has dropped from 4.5 per cent to 2 per cent.

Many managers are significantly underweight the most troubled economies. Matt Ryan, co manager of the MFS EM bond fund, is 3 per cent underweight Venezuela, with a 4.8 per cent holding, which meant he missed the gains made last year.

“The Venezuelan government has been pursuing unsustainable policies for years, and that mismanagement is finally coming home to roost,” he says. “The market rallied earlier this year on the prospect for reform measures, but so far there’s been more talk than action.”

Sentiment has been forgiving though, and Venezuelan bonds saw a strong run during the last few months, but Mr Ryan does not think this will last. Fiscal deficits remain large and the central bank continues to print money at an excessive pace.

Growth in Venezuela is negative, there is social and political unrest, and low liquid reserves, which are mostly in gold that cannot be borrowed against. Efforts to implement flexibility in exchange rates were not followed through with fiscal and monetary restraint, he explains.

“Nor is the new FX regime run in a transparent manner. Allowing the currency to find an equilibrium would be good, but they still need to tighten fiscal and monetary policies or money will still leave the country and credit worthiness will continue to decline.”

One trend emerging from the diversity in performances is that EM debt is no longer considered a single asset class play. The industry is talking up the need for active security selection across geographies and the fixed interest spectrum of bonds, CDS, loans and convertibles.

“EM debt will become much less of a beta play given the changing character of the liquidity and investor composition,” says Invesco’s Mr Deino. “It needs very strong active managers, but achieving solid single digit returns in a world of low rates is not such a bad place to be.”

Fund managers are paying particular attention to governments with a reforming agenda. “A lot of EM debt generally looks expensive but we like markets which because of the sell-off have been repriced and are starting to look attractive, in particular where government policy is changing,” says Christopher Wyke, Schroders’ emerging market debt product manager. He thinks that Brazil, Vietnam, India and Indonesia are countries where, despite the big sell-off, the fundamentals are fine.

India is particularly popular as a market that has been sold off sharply and has suffered 40 per cent devaluation in its currency, but has a new prime minister in Narendra Modi and an able new central bank governor at the helm. Mexico is also a crowded trade, as investors warm to the a raft of reforms to attract foreign investment in a world with more competition, such as in energy, education, and telecoms.

However the ‘go-anywhere’ Schroders fund holds zero in corporate bonds because of the credit and liquidity risks. “While many other funds are heavily invested in corporate bonds, we think corporate bonds are over expensive and many companies have launched them recently and clearly not all credits are good quality,” says Mr Wyke. “But liquidity is the bigger risk – when markets fall, most of these bonds are new issues, not seasoned bonds bought in the secondary markets, and so when they fall – like in last May, June, August, October and January this year, the liquidity in the sector also fell off. Even if you do your credit analysis well, the danger is you cannot sell your assets. The situation has been made worse too by banks devoting less capital to market making than eight years ago.”

One way to measure liquidity constraints is to look at the number of firm quotes in the market and at the bid/ask spread which can widen to 3-4 points, which almost becomes trading by appointment.

Investment in frontier markets is also gaining traction. ING’s frontier markets fund made 10 per cent in its first eight months since launch in December. Bond holders are able to get more diversification in Africa than before, says Roy Scheepe, senior client portfolio manager emerging markets debt at ING IM. “If you look at hard currency funds, over the last 10 years our fund has made about 12 per cent to 13.5 per cent on an annual basis. If you believe frontier markets will make the same progress, then you should buy into them now.”

Balancing risk and reward

“We generally favour adding emerging market debt as part of a diversified bond portfolio to enhance the overall risk/reward proposition,” says Pierre Bose, head of fixed income, Europe at Coutts.

The firm has a bias to hard currency over local currency debt. FX risk and returns have been less predictable than credit over the past 12 months, he explains, and focuses selection on securities with higher quality credit ratings and on medium-term maturities. “Each ‘layer’ of country/sector/company exposure is an additional risk factor explaining the higher yields on offer and this is why we prefer active over passive management via both third party managers and our own direct research,” adds Mr Bose.

FX risk has become a bigger risk than credit risk, he warns, and since currency explains three quarters of returns, clients looking at local currency bonds must be comfortable with it.

Since Lehman, most of Coutts’ focus has been on developed markets in investment grade – where good spreads have been available on blue chips. But Mr Bose believes that now European spreads are less than 100 bspts, arguably investors are paid too little for the risk. “In the last six to nine months we have been looking at enhancing yield – taking a very broad view, and selectively picking the better credits. There is enough hard currency, investment grade offering spreads of 200-400 bspts without reaching down to the BB or CCC credits and we can for example focus on hard currency in majority state-owned enterprises.”

Some of the high yield names with CCC credit ratings will find it challenging to roll over their debt given many investors’ investment rating restrictions. For example, many funds on insurance platforms are not allowed to invest in countries rated below BB.

VIEW FROM MORNINGSTAR: Partial recovery

Emerging market bonds partly recovered from last year’s correction over the first seven months of 2014.

While many leading indicators are pointing to a moderate improvement in global growth, many emerging countries remain fiscally prudent but have resorted to easing monetary policy as a means to tackle weak growth (as evidenced in the second quarter by cuts in interest rates in Turkey, Mexico and Hungary), which benefited bond markets this year.

Many emerging countries remain fiscally prudent but have resorted to easing monetary policy as a means to tackle weak growth, which benefited bond markets this year

It has not, however, been a smooth ride for all emerging market debt investors. The recent geopolitical turmoil between Russia and Ukraine added volatility, while Argentina’s struggles to avoid technical default made the headlines repeatedly, even if the global response from financial markets was relatively muted.

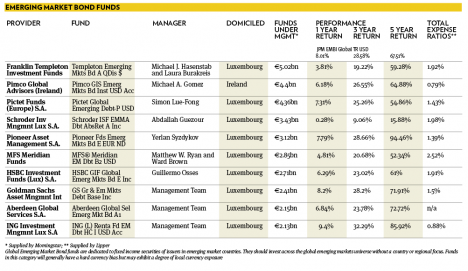

Templeton Emerging Mkts Bd (with a Morningstar Analyst Rating of Silver) had a difficult run over the past 12 months, returning only 3.81 per cent (in euro) annualised, compared to 7 per cent for the Morningstar Global Emerging Markets Bond category.

Manager Michael Hasenstab, who has been running this strategy since 2002, uses an unconstrained approach that seeks to uncover value in bond and currency markets through rigorous macroeconomic analysis at the country level. The flexible nature of this process means the fund’s composition and performance can differ from that of the benchmark. In particular, a meaningful proportion of assets are invested in local currency emerging market bonds (47 per cent as of May 2014, the most noteworthy being the Korean won and Malaysian ringgit).

While this approach has delivered attractive returns for investors over the long term, it comes hand in hand with higher volatility. The fund’s bold country and currency bets may also entail periods of significant underperformance: since the beginning of 2014, the fund’s 7 per cent exposure to Ukraine detracted from returns.

Pictet Global Emerging Debt (with a Morningstar Analyst Rating of Bronze) outperformed the category over the first half of 2014, after a disappointing 2013. The fund has been managed by a new team, which arrived from Fischer Francis Trees & Watts, a subsidiary of BNP Paribas, since July 2012. The investment process is comprehensive in covering both global and country-level drivers of emerging-markets bond performance, and focuses on limiting losses.

With a rather cautious positioning, the fund was well positioned to withstand last year’s market correction. However, in September 2013, it was caught off-guard by the decision of the US Federal Reserve to delay the tightening of its monetary policy, causing the bonds and currencies of developing countries to rally considerably. The fund was hampered by short positions in emerging-markets currencies and its shortened duration and it trailed the competition overall in 2013. It has, however, fared better in 2014, aided by under-exposure to Russia (including quasi-sovereigns).

Mara Dobrescu, fund analyst, Morningstar