Rout subsides to reveal opportunities in emerging market bonds

Niamh Wylie, Coutts

Emerging market bonds have always been volatile and the Fed’s comments about the end of QE saw large numbers of retail investors flee the asset class. But there is a sense the market overreacted and the sell off has created a buying opportunity

Emerging market bonds made 16 per cent last year in dollar terms, but have endured a bloodbath this year since the US Federal Reserve started to discuss when to scale back quantative easing (QE), potentially sending interest rates higher.

Investors, particularly retail savers, exited these markets in their droves. In the month following the 19 June Federal Reserve meeting when the taper was first mooted, emerging market bond funds saw outflows equivalent to almost 3 per cent of their assets under management, according to funds data specialist EPFR, and corporate issuance dried up.

Ten-year Treasury yields hit a two year high of 2.75 per cent on 8 July, but fell back after Fed chairman Bernanke quelled concern that a reduction of monetary stimulus was imminent. At their current levels of 250-260 basis points, they still leave plenty of flexibility compared with pre-Lehman levels of 3-4 per cent.

A lot will depend on how fast the taper takes place and the market will be watchful for developments in economic data and the labour market. There is a case to start scaling back in September but not if there are any big downgrades in the Fed’s forecasts.

Unusually, Treasury yields have risen at the same time as the spread on the index has widened. “There are two reasons for that behavior,” says Ward Brown, investment officer at MFS. “Firstly, even 2.5 per cent is still an unreasonably low yield for Treasuries which historically are 3-4 per cent. And secondly, liquidity is thin in emerging markets. Secondary markets have never really recovered since Lehman in terms of volumes, but investment in the asset class has grown dramatically, so price moves tend to be exaggerated.”

Although the asset class has always been volatile, the underlying fundamentals are excellent, and there is a sense markets have overreacted. Some institutional money has been quick to come back in at the right price point. Goldman Sachs AM for example has been active in buying emerging market bonds on the dips, particularly in Brazil and Mexico.

“Funds experienced a blanket sell off in May and June of this year, but movements of this magnitude are not atypical of this asset class,” says Niamh Wylie, portfolio manager at Coutts. “Emerging market bond funds are prone to volatility. For example we hold the BlueBay fund and it regularly has sharp sell offs but has then recovered and moved higher. In 2006 and from 2010 onwards, within each year a drawdown occurred of between 7 per cent and 10 per cent,” she says.

Key re-ratings

• Mexico: Re-rated to investment grade (BBB-) in 2002, now BBB

• Brazil: Re-rated to investment grade (BBB-) in 2008, now BBB

• Colombia: Re-rated to investment grade in 2011, now BBB

• Indonesia: Re-rated to investment grade in Jan 2013

• Philippines: Re-rated to investment grade March 2013

“Historically, it has been the wrong time to sell after these corrections. There is also the long term case for investing in sovereign EM debt in the shape of its strong credit fundamentals versus deteriorating fundamentals in the developed world so we are sticking with our position. Many developed market sovereigns have been downgraded, most recently Italy, whilst the trajectory has been upward for credit re-ratings in emerging markets.”

Examples of countries re-rated in recent years include Brazil and Colombia and in 2013 Indonesia and the Philippines.

However, David Spegel, global head of emerging markets strategy at ING, says the credit picture for emerging markets is fairly neutral, with the net credit ratings trend moving sideways, and occasional net upgrades in some quarters followed by downgrades in others.

“We saw three more sovereign upgrades in the second quarter 2013, which followed 10 net downgrades in the first quarter, zero in the fourth quarter 2012 and 10 net upgrades in the quarter prior to that,” he says.

However, the outlook remains less certain, predicts Mr Spegel. “We will probably see credit risks deteriorate slightly going forward in light of emerging markets’ shrinking current account surpluses as well as given our expectation that there will be an increase in defaults rates going forward. But, we are not talking about an end to the emerging market world, here. All we are seeing are some bumps along the path of emerging markets’ convergence with developed markets as the world readjusts to the new global growth paradigm tied to Europe, Japan and China and as fixed income markets prepare for reduced QE in the US.”

On the corporate debt front, there have been 15 corporate defaults in emerging markets (to mid-July) and another 11 are expected, and on secondary markets spreads are rising showing the risk of default. Last year there were 33 defaults in euroclearable debt. Mr Spegel expects a corporate default in Colombia by Codere, the Bakrie-land development and telecoms companies in Indonesia and rising prospects for defaults by NYC law quasi-sovereigns in Argentina.

Dollar debt

A clear preference has developed for dollar-denominated debt over local currency debt. “Local currency bonds are down 6 per cent year to date – two thirds of that drop has been caused by the currency sell-off,” says Oliver Gregson, global head of discretionary portfolio management at Barclays Wealth.

“Following the events of the global financial crisis, many emerging market nations have opened bilateral trade agreements and issued more debt denominated in local currency in recent years in an endeavour to mitigate the impact of these events in the future. This has been aided by the chase for yield and concomitant demand from investors for these type of securities in a low interest rate environment. Those countries with big current account deficits such as Turkey, South Africa and Brazil have fallen by double digits in the recent sell-off and flight to quality.”

The moderation of China’s growth to perhaps just 4 per cent, against previous expectations of 7 per cent, will increase the convexity of the market, but there is still an emphasis on differentiation between countries.

“One can like the fundamentals of countries without liking their currencies, so we are primarily buying hard currency bonds as most clients are not looking to take on currency risk,” says Paul DeNoon, partner at AllianceBernstein.

“Some countries have done a better job. In Latin America, for example, we are most positive on Mexico, Chile, Peru and Colombia and in Emea we are still optimistic on Turkey and Poland, while in Asia the Philippines is the standout as its package of reforms and macro economic management has been well handled and the country is also less exposed to global liquidity conditions.”

Mexico is favoured by several fund managers. President Enrique Peña Nieto is keen on reforming the economy, such as opening up the mobile market which should help bring inflation down and has unveiled a huge MXN4tn (€237bn) infrastructure investment plan between 2013 and 2018. Last year Chinese labour costs rose above Mexican costs because the one child policy means fewer entering the Chinese workforce than are leaving it, which boosts the competitiveness of Mexico’s manufacturers.

Some of the smaller countries also offer good opportunities. For example, Brett Diment, head of emerging market and sovereign debt at Aberdeen Asset Management, says the debt to GDP ratio is 16 per cent in Nigeria and 39 per cent in Lithuania and they have a relatively high capacity to pay. Similarly, Aberdeen holds a sovereign inflation-linked bond in Uruguay, a country that is now a larger beef exporter than Argentina, and whose high growth rate could lead to higher inflation. Mr Diment points out that these holdings have different drivers and therefore offer some diversification protection – for example, Lithuania is driven by good economic management, Nigeria is driven by oil, and Uruguay is driven by soft commodities.

The hunt for yield

Investors are differentiating between high yield and high grade. Uta Fehm, senior portfolio manager for emerging market debt at UBS Global Asset Management, says: “We still prefer high yield issuers such as Argentina, Venezuela or Belarus with spreads around 600-900 basis points over high grade issuers like Brazil, China and Mexico, which are on spreads of 100-120 basis points. We also like quasi-government issues such as Petrobras or Pemex, which are owned partly by the government so have similar risks to sovereigns but higher spreads. Higher spreads give us a cushion in case yields go up further and will outweigh negative effects partly.”

One consequence of the universal hunt for yield has been to put a strain on liquidity. Most retail funds trade daily. Market-making banks also face big challenges as a panoply of new regulations make it expensive to hold debt, and bank bond inventories have fallen 77 per cent from about $235bn in 2007.

Liquidity is also constrained by the proliferation of issues from corporates that are infrequently traded, and the mass outflows in June also highlighted the attraction of establishing electronic trading platforms to match buyers and sellers in the bond space.

Shifting allocations

Wealth managers tend to like active funds in imperfect emerging markets and keep both currency-hedged and non-hedged funds on their panel so that clients can choose whichever best suits their circumstances.

Barclays Wealth recently decreased its allocation to high yield/emerging markets debt to underweight from neutral and, according to Oliver Gregson, global head of discretionary portfolio management, is holding the proceeds in cash until visibility improves.

Niamh Wylie, portfolio manager at Coutts, thinks the taper will be gradual and the asset class is attractive although it may take some time to restore confidence. However, Norges, the Norwegian pension fund, made an allocation to the sector recently, and in Indonesia a new $1bn (€0.75bn) sovereign issue was twice oversubscribed, with 75 per cent of demand from investors outside the country.

“This is evidence of a return of risk appetite, and in the case of Norges, it is long-term money, not hot money,” she said. “What we can see is that investors are looking to use emerging market bonds in lieu of emerging market equities. Since 2001 emerging market equities have returned 12.6 per cent on an annualised basis, while emerging market bonds have delivered 12.4 per cent – there is not a lot in it but of course bonds have the better risk /reward profile.”

View from Morningstar

Severe correction

After their strong run in 2012, emerging market bonds underwent a severe correction over the first six months of 2013, with the JP Morgan EMBI Global index losing -6.9 per cent (EUR) up to the end of June 2013.

Following the Federal Reserve’s announcements of a reduction in quantitative easing, some of the capital flows that had buoyed emerging markets debt during periods of low rates in developed economies have now started to pull out. At the same time, the perceived slowdown of growth in several of the largest emerging economies, combined with concerns on increased funding costs in an environment of lower liquidity than in the past, have accelerated the re-pricing of emerging market debt. Over the period, longer-maturity issues suffered the most, particularly in emerging Asia, while shorter-dated paper came through relatively unscathed.

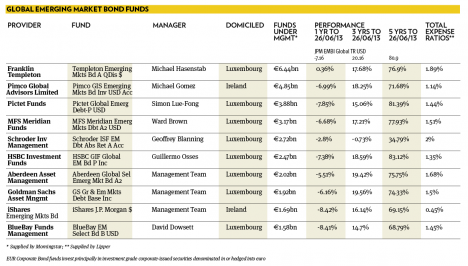

Templeton Emerging Mkts Bd was one of the very few funds in the Morningstar Global Emerging Market Bonds category to deliver positive performance (0.36 per cent over the period ranging from July 2012 to July 2013). Manager Michael Hasenstab, has been running this fund since 2002, using an unconstrained approach that seeks to uncover value in bond and currency markets through rigorous macroeconomic analysis at the country level. The flexible nature of this process means the fund’s composition and performance can differ from that of the benchmark. In particular, a meaningful proportion of assets are invested in local currency emerging market bonds.

As of May 2013, the main country bets were concentrated on Mexico, followed by Nigeria and Uruguay. In the past, the fund had tended to do worse than competitors during sell-offs. Yet country selection and currency positioning proved successful over the first half of 2013, while the short duration also helped.

BGF Emerging Markets Bond lost -7.01 per cent over the last 12 months. The fund has been managed by a new team since July 2012, who arrived from Fisher Francis Trees & Watts, a subsidiary of BNP Paribas, and is led by Sergio Trigo Paz. The investment process is comprehensive in covering both global and country-level drivers of emerging-markets bond performance. Yet, over the 12-month period since the team has been responsible it has slightly underperformed competitor funds, while being more volatile. Over the second half of 2012, the portfolio’s large overweighting in Argentina had hurt. In 2013 the team partly repositioned the portfolio based on a more prudent outlook for emerging market bonds, buying US Treasuries and reducing the fund’s duration, which limited losses.

MFS Meridian Emerging Markets Debt posted a -6.7 per cent loss over the past 12 months, which is disappointing in absolute terms, although the fund has done slightly better than its category average. The fund is managed by Matthew Ryan and Ward Brown, both former IMF economists, who are supported by two experienced sovereign analysts. The managers have been eschewing low-beta, low-yielding investment-grade sovereigns, which they felt had been trading at relatively full valuations. Instead, they have been emphasising higher-yielding sovereigns and select corporate bonds. They were underexposed toward Brazil and Mexico but overweighed Venezuela and Argentina (which hurt over the last half of 2012).

Mara Dobrescu, senior fund analyst, Morningstar France