Political pressures put investors off emerging market equities

Recent sell-offs in emerging market equities have been dramatic, but most fund managers believe the asset class remains a compelling long-term investment

While recent falls in emerging market equities have been sharp, it is easy to forget these assets have underperformed their developed market counterparts for three years, with the Federal Reserve’s decision to taper last May acting as a damaging catalyst and China’s economy transformed from growth driver to major cause for concern. While emerging economy stocks are trading at around a 30 per cent discount to developed economies, in October 2010 they were at a 20 per cent premium.

“Before the talk of the taper, investors papered over the developing world’s structural cracks,” says Derrick Irwin, portfolio manager at Wells Fargo Asset Management. “For example, in late 2012 no one would discuss the risks in Turkey’s current account deficit – it was not seen as relevant. In May that changed and the world saw in sharp relief the risks in the structural problems. Previously, the general standpoint was that there was not a great deal of country specific performance but since May there has been strong dispersion between countries, related in part to their current accounts.”

The depth of the recent sell-off – weekly outflows reached $6bn (€4.3bn) in February – was accompanied by panic among even sophisticated institutional investors. Global equity managers for example now have the least in emerging markets relative to Europe for the last 14 years.

Capital outflows from emerging market funds for the first five to six weeks of 2014 were $15bn compared with a total of $27bn for all of last year, says Julian Mayo, co-CIO at Charlemagne Capital. “That looks like capitulation. There is now a classic case for pound cost averaging re-entry into the market.”

For most fund managers, however, the sell-off has not changed the essential view of emerging markets as an enduring investment opportunity involved in a multi-generational process of convergence with the developed world.

“My sense is that it is mostly European financial institutions, including private wealth managers and retail investors on large platforms, exiting,” says Mark Gordon-James, senior investment manager on the Aberdeen Global Emerging Markets team. “These are supposedly long-term investors, who are questioning the very rationale for the asset class, which is clearly ridiculous.”

He admits emerging markets have disappointed for a few years now, and weakening currencies and capital flight have knocked confidence in recent months. But Mr Gordon-James argues this is a necessary period of adjustment that will place them on a more solid economic footing for the future. “Credit expansion is slowing, current account deficits are narrowing, currencies are now more competitive, and politicians are being compelled to reinvigorate policies to attract inward investment and sustain growth. So the principal investment case very much remains; while these countries have less mature institutions and suffer occasional political crises, the positive trajectory remains intact – they are coming from a low base and have significant growth potential.”

What has changed in the last year is the focus on the political backdrop that some investors had previously overlooked, an awareness heightened by the imminent elections in a string of nations including India, Brazil, South Africa, Columbia, Thailand and Indonesia.

“The region’s problems are largely political,” says William Calvert, investment fund manager at Polar Capital. “While the last 10 years have seen a credit-fuelled consumer boom, there is now a need to switch to investment growth, to inspire businesses to invest. In India there is optimism as the incumbent will definitely not form the next government so we should see a dramatic break from last year. In South Africa there is the growing story of attempts to find a way of pushing President Zuma aside in return for immunity from prosecution. In Brazil, the government looks set to win but president Dilma Rousseff comes from a far left background and may not want to wield an axe to spending.”

India is among the countries where a possible change of government could unlock growth. Its trade balance has improved massively over the past eight months, but the cap to its potential is that new investment projects as a percentage of GDP have fallen, from 40 per cent in 2007-9 to just 5 per cent.

“India is an interesting opportunity but much of the optimism is priced in, and change is not in India’s DNA,” adds Mr Calvert. “The opposition Bharatiya Janata Party, led by Narendra Modi, trounced congress in recent state polls taking 200 plus seats and he is business friendly, pro-infrastructure and investment. The country needs a government that will deal with the bureaucracy. Take Petronet – utilisation of its gas facility south of the country is low because the gap pipeline has not been built because farmers are upset it will go over their land.”

Many fund managers cite Merrill Lynch’s recent research on stock valuations in emerging markets, which found extreme polarisation with some companies overly expensive and some very cheap. For example, Petrobras is trading at 0.7 X book value compared with 3.5 X book value in 2007, while at other extreme Tencent trades on a PE of 40. The Merrill paper essentially portrayed stocks as either expensive or rubbish, as the good companies have been well identified, particularly domestic consumer-facing companies, and were rerated in 2010-2012.

That has since rotated into tech names and exporters which have become expensive. “Investors are only interested in cast iron growth stories such as the internet and those that export to the West,” adds Mr Calvert. “Tencent’s spectacular rerating means it is 10 per cent of the index. So what do you buy?”

It can leave investors looking for opportunities in new regulations and political developments. In India, for example, the government could lift subsidies in oil, which would boost revenues at Oil and Natural Gas Corp.

Surveys show us that emerging markets are the most hated asset geography

“Surveys like Merrill Lynch’s Global Investors show us that emerging markets are the most hated asset geography,” says Jean Médecin, a member of the investment committee at Carmignac Gestion. “We are more constructive now than 18 months ago, but think this is only the beginning of the improvement. In extreme cases such as the end of the 1990s after the Asian and Russian crises, EM valuations went to a 40 per cent discount to developed markets so they are not already a ‘screaming buy’.”

Mr Médecin believes three triggers could provide a catalyst for EM outperformance. Historically there have been good correlations between industrial production in Western and emerging economies. Over the past quarter there has been a pick up in Western countries that has not been matched by the EM world, which is something to watch closely.

“Secondly, divergence between operating margins in companies in EM and developed world has been building in the last one to two years. Part of the reason is that wage inflation has not been matched by pricing power. The pick up in economic activity and benefits from weaker currency are helping EM countries to rebuild their competitiveness providing scope to improve profitability,” says Mr Médecin.

He argues that reforms in countries such as Mexico and China augur well for the future. “Mexico has the strongest visibility in term of reforms such as the liberalisation of media and telecoms, and the energy sector allowing private companies to start participating. Mexico also enjoys an orthodox macroeconomic policy and significant credibility. One of the few central banks to be able to lower rates last year and boasting strong and prudent fiscal management, it has been upgraded by Moodys.”

In China, which is currently on price to book of 1.45 compared with 1.2 in 2008, the main theme is the new leadership’s call for a ‘decisive’ role of the market in the economy, for example to set interest rates. However, there is massive overcapacity in industry and it is also environmentally destructive. The government, though, is falling in line with public opinion on the environment and corruption, and the two are not entirely unrelated.

Countries which are setting a scene where they can be viewed positively will get inordinately expensive, says Mr Irwin at Wells Fargo. “There is a big differentiation between countries, and how they are responding to structural challenges. For example Brazil has been very slow to implement changes to address structural imbalances. In particular there is a need to address the government influence in the market, such as its meddling with Petrobras.”

He adds that many fund managers are hiding in Korea and Taiwan, a view shared by Gabriel Wallach, portfolio manager at BNP Paribas. “Many of our competitors are overweight in Mexico and Korea and have also turned to exporters which they perceive to be defensive,” he says.

The investor base in emerging markets is concerned about global and domestic growth and so they are very defensive and hiding out in markets that will benefit from developed market recovery, believes Mr Wallach.

“We think the opposite – we see a recovery in traditional growth sector that has not performed as well recently such as India, Indonesia, Brazil and China,” he explains. “These countries had to raise rates aggressively last year as a response to the taper and inflation and also saw it as a good way to slow imports to help deal with the current account deficit. The rate cycle is peaking, current accounts are closing and currencies have stabilised. We like banks, such as Bank Mandiri, Hdfc and Bank Itaú, which have been growing at the rate of 15-25 per cent pa and have high returns on equity but were sold off last year.”

Mr Wallach also likes UEA and Qatar which have been uprated to emerging market status.

Most fund managers are focused on individual stock opportunities, but Schroders claims that country allocation is a central part of its process and has historically accounted for 50-75 per cent of returns.

“Divergence between countries continues to be large,” says Allan Conway, head of emerging market equities at the firm. “In the EM world most years the best country is up 100 per cent and the worst is down 50 per cent or more. Last year for example Egypt was up 22 per cent, Turkey was down 30 per cent and Chile was down 32 per cent. There has been some convergence but it will take a very long time. Just think about the integration of Europe which required the EU and the Euro before the country factor became pretty much irrelevant.”

Mr Conway thinks the ‘Fragile Five’ – Brazil, Turkey, India, Indonesia and South Africa – are indeed fragile and their interest rates need to rise further. He prefers the ‘Fab Four’ – China, Russia, Korea and Taiwan – whose strong current account positions make them less reliant on foreign capital to finance debt and less sensitive to interest rates.

Time for a spell on the sidelines

Ben Gutteridge, head of fund research at Brewin Dolphin wealth management, is concerned about the dependence of emerging markets on foreign capital, which is one of the last pillars of support for this asset class given the deteriorating fundamentals and unattractive valuations.

“It is often proposed that, despite the associated increase in price volatility, high, if waning, growth levels should win out in the long run, and help deliver superior returns,” he says. But could it be that this last bastion of support is starting to crumble, suggests Mr Gutteridge, pointing to the enormous outflows.

Unless weak US data forces the Fed to deviate from its path, the taper will stir a gradual rise in bond yields, sending the cost of capital higher worldwide. This would prove particularly painful for the ‘Fragile Five’ – Brazil, Turkey, India, Indonesia and South Africa – that run current account deficits and are dependent on external funding.

The situation for Turkey and South Africa, which have acquired large amounts of foreign denominated debt, is even more acute

“The situation for Turkey and South Africa, which have acquired large amounts of foreign denominated debt, is even more acute,” says Mr Gutteridge.

For an economy to find its equilibrium, he explains, imports should roughly equal exports, and to achieve this ‘current account deficit’ countries should allow their currencies to weaken. This would inflate the cost of imports and encourage domestic substitution, as well as boosting exports. Not only does this generate higher levels of inflation however – cue civil unrest – it also makes the servicing of dollar-denominated increasingly challenging.

To defend their respective currencies, the South African and Turkish central banks have both enacted emergency interest rate rises, in the hope the increased yield would stall capital flight, says Mr Gutteridge. Relief proved only temporary, however, as markets looked through the noise and focused on the negative connotations of higher borrowing costs on domestic growth.

“Admittedly there is hope their elections may bring reform but, more likely, they will usher in yet more socialist policies from unpopular incumbent governments,” he adds.

Combine these issues with the increased scrutiny of the Chinese shadow banking system, in which souring loans are gaining increased attention, and Mr Gutteridge suggests investors should for the time being sit these markets out.

View from Morningstar: Good times come to an abrupt end

After years of robust outperformance, emerging market equities were one of the worst places to be invested in 2013. Over the 12-month period ending March 1, 2014, the MSCI EM NR index lost 11.03 per cent in euro terms, while the S&P500 NR and the MSCI World NR posted gains of 17.93 per cent and 15.18 per cent, respectively.

Beyond the worsening of certain fundamental factors (lower than expected GDP growth, political risk uncertainty, or balance-of-payment deterioration in some individual countries such as Turkey or Argentina), emerging markets were globally hit by the Federal Reserve’s initial tapering announcements in May 2013.

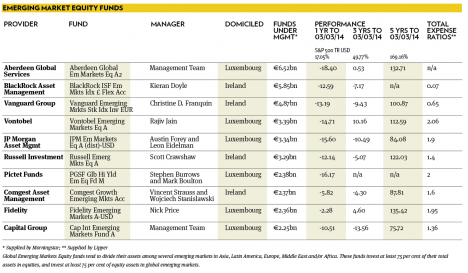

Having been one of the main beneficiaries of the abundant liquidity conditions that have prevailed in recent years, emerging markets are naturally suffering from a shift in investors’ sentiment regarding a less permissive monetary policy going forward. Yet, investors have proved, so far, quite selective and although the Morningstar Emerging Markets Equity category lost on average 11.85 per cent over the period, there have been noticeable differences in performance among funds in this category.

Gold-rated Comgest Growth Emerging Markets managed to limit its losses to 5.82 per cent over the last 12-month period ending March 1, 2014. The fund ranks top quartile over that period and that outperformance is fully in keeping with what investors should expect from Comgest’s disciplined and proven approach to investing. This fund focuses on highly profitable companies which the team believes can continue to grow independently of the economic cycle. Therefore, highly cyclical companies and financials are generally excluded from the investment universe, and the fund tends to do well on a relative basis in downward markets.

At the other end of the performance spectrum, Aberdeen Global Emerging Markets, which also boasts a Morningstar Analyst Rating of Gold, underperformed its peers, losing 18.4 per cent in euro terms over the period. The fund’s longer term risk-return trade-off remains outstanding, and one bad year of performance has not dented our conviction in its potential on a full market cycle. It benefits from one of the best resourced teams dedicated to this asset class and a robust process that has been applied consistently through time. The team emphasises both value and attention to corporate governance. For that reason, it tends to be less exposed than peers to countries such as China and Russia, which was a key detractor to performance in 2013.