‘Global gorillas’ reach for the stars

Fund distribution is changing. A number of “global gorillas” are expanding through acquisition to dominate the cross-border space while other banks look to dominate their domestic markets. But does this benefit investors?

A consolidating, futuristic landscape for wealth management and distribution is emerging from the changes to the industry’s vulnerable climate.

A new kind of distribution beast is evolving from the cross-winds of regulation, the increased pressure on costs and the swirling fund flows through developing regions that shape structures of funds and banks.

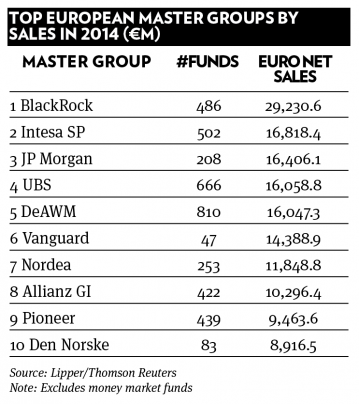

“There are a small number of very large intermediaries, such as UBS, JP Morgan and Credit Suisse, emerging to dominate the market,” says Jim McCaughan, CEO of Principal Global Investors. “They are all growing in power, offering good technology and lower fees.”

The industry’s inexorable shift in this direction will not be without turmoil, he believes. “There is a lot of potential disruption by start-ups on they way,” with robo-advisers ready to play a crucial role.

76,669

There are almost 80,000 mutual funds worldwide, according to the International Investment Funds Association, of which more than 35,000 are in Europe

The next stage of this gripping story will see all major banks digitising distribution platforms to allow a much broader army of investors to access products, predicts Diana Mackay, CEO of funds consultancy Mackay Williams. “You will see banks moving into the robo-advice arena. This is exactly where they need to be.”

Development in this area has so far been slow, particularly in the UK. But banks are finding the whole concept of offering advice difficult to manage, says Ms Mackay, with a no-strings-attached “robo-advice service” currently better suited to today’s more impersonal banking mindset.

Big banks can tweak such offerings for each individual country market. Local language instructions and selections of funds can cater to regional investment tastes.

“You can have the same platform, but it needs to be fine-tuned for a local market,” she says. “As we become more the same over time, that is naturally the direction of travel.”

While technology must play a vital role in these transformations, the most successful distribution platforms will also be utilising more human skills to acquire customers.

“The institution in private banking that can combine information technology, to ensure scalability and consistency, with a high focus on quality, advice and insight, should be the natural winner,” says James Bevan, head of investments at charity specialists CCLA, currently preparing offerings for the family office and private client spaces.

A “significant leap forward” by players such as Goldman Sachs, which has developed IT and risk management tools in investment banking, can be leveraged for wealth management. Wells Fargo’s newly-defined business model is also worthy of note, says Mr Bevan.

Well-established banks now face less competition than before the global crisis and consequently, opportunities available for distribution should be greater.

The most successful players will enable access through both physical and virtual channels, believes Cara Williams, global head of wealth management and technology solutions at consultancy Mercer.

“All the models can co-exist for a good long while,” she says. “Some say we will have no private bankers in 20 years, that robo-advisers will take over, but some clients will always want personal advisers. Even the wired, younger generation still want more human interaction as they get older.”

The biggest players must offer both a technology option and a human option. Increasing flexibility to switch between the two will become a key differentiator between banks.

Although some banks will deploy advanced technology they have developed solely in their home market, there is nothing to prevent these state-of-the-art solutions being sold to banks chasing different customers in other parts of the globe.

Tech-savvy Korean banks such as Hana will epitomise this new, home-focused vanguard, says Ms Williams. “I would imagine the benefit there is to sell the technology to others firms rather than actually expand internationally,” she says.

“There is so much to understanding cultures of local investors and I am not sure the Koreans have mastered that. But developing the technology, selling it and looking at how to apply it to various markets – that could be a very powerful model for them.”

The most successful global private banking players will be those that can mix and match the best of everything, “to identify all the different pieces you need, to identify the innovation hubs and turn it all into a cohesive operation. There is not one single turnkey solution that fits everything,” states Ms Williams.

Meanwhile, often backward-seeming European private banks have still to embrace positive concepts such as outsourcing. “The growth of the Avaloqs of this world, with their operational infrastructure, provides a way for those who are not giants to survive. Nobody can do everything anymore.”

The futuristic distribution landscape which Ms Williams vividly paints is dominated by between five and 10 “global gorillas”, almost all of them European, who will continue to grow by acquisition to claim the cross-border space, while US giants in particular retrench back home.

“I don’t see Wells Fargo or Bank of America in there,’ she says. “Only the Europeans are going for global expansion, as they don’t have the population to grow domestically.”

This trend will run in parallel to that of other top private banking franchises slimming down to preserve their brand in a more limited marketplace. “While global gorillas seek world domination, other banks, such as Coutts, want to be market gorillas in their own habitat of the UK.”

Few leading US private banks by AuM scale are cross-border focused, confirms Seb Dovey, founder of wealth management think-tank Scorpio Partnership. BAML is a single market player and Morgan Stanley is dominated by its US domestic business, even if it boasts an Apac private client division, says Mr Dovey.

UBS “sets the standard” for cross-border activity, with assets of wealthy individuals increasingly concentrated in the hands of 10 global private banking institutions, which Scorpio calculates hold 48 per cent of the active market, worth $9.9tn (€8.9tn).

“This distribution power among the HNW/UHNW marketplace is substantial,” he says. “I would suggest private banks would like more of a cross-border distribution platform, but it is easier said than done.”

BACK IN THE GAME

If there is one major change in 20015, it is that the big banks are now “back in the game”, suggests Ms Mackay. “They are all selling funds again. Asset management has suddenly switched from being a bit of a pariah to a profitable opportunity.”

Banks have decided they no longer need a cash reserve and are looking for ways to rebuild profitability. Asset management, and selling funds in particular, is emerging as a prime option for them. “It makes sense that the likes of Credit Suisse are looking at this all over again,” says Ms Mackay.

PWM's fund selection

• Each month in PWM, nine top European asset allocators reveal how they would spend €100,000 in a fund supermarket for a fairly conservative client with a balanced strategy

• The fund selectors represent AA Advisors, Aviva Investors, Eurizon Capital, BMO Global Asset Management, Fundquest from the BNP Paribas Group, SGPB Hambros, Invesco, Santander and SEB Asset Management

• Combined they manage in excess of €2.7tn

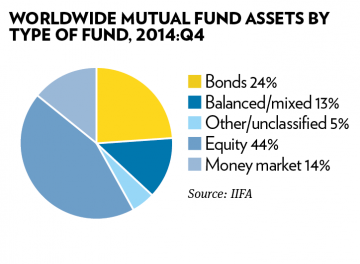

Moreover, Europe finds itself in the midst of a massive shift back to the equity culture, fuelling huge flows into investment, confirms Peter De Proft, director general of the continent’s fund managers’ association, Efama.

“The flows started with institutional investors and then spread right down to the retail industry,” says Mr De Proft. “It is strange how things can change in a couple of years, but the whole environment is now different.”

There are three factors he identifies responsible for this mindset change: low interest rates making bank deposits unattractive, a more level regulatory playing field for funds versus structured and insurance products plus a digitally innovating distribution landscape, allowing private clients faster direct access to funds.

But fast-improving quality of investment institutions might also be responsible for fostering trust and attracting more money into the industry.

“There is a big change in leadership going on,” says Principal’s Jim McCaughan. “The people who have changed their model are the ones winning business,” focusing on the “fertile ground” of multi-asset solutions.

“The investment industry is no longer about finding growth stock portfolios,” he says. “Those firms have been displaced or beaten back by passive players. Now we are talking about finding solutions for savers. People who used to buy into the dream of large cap equity portfolios 15 years ago are now investing into multi-asset or passive funds.”

While some private banks are still using up to 400 investment managers, most have cut-back severely, for reasons of scale and efficiency, says Mr McCaughan, with many disgruntled fund houses stranded on the wrong side of these rationalisations.

The resulting pattern leaves 80 per cent of business flowing to 10 managers with the most resilient brands, he says.

Fund selector facts

• PWM’s nine fund selectors used 72 asset management brands to build the monthly €100,000 portfolio for a fairly conservative client with a balanced strategy over the first six months of 2015

• The fund selectors selected 136 funds over the past six months. Each fund selector has used 14 funds monthly on average to build their portfolio

• Over the past six months, the selectors invested around 57 per cent of total fund assets in equities (mainly European and US), 24 per cent in fixed income, 17 per cent in alternatives, mainly hedge funds, and 2 per cent in cash

“Private banks created fund selection teams and they all struggled with the same business model of trying to choose the best performing managers from the previous year,” he says. “Most ended up doing no better than retail investors.”

This is no longer good enough for demanding clients, who expect to see prudence of selection criteria being applied, embracing consistent investment performance, value for money and governance, says Scorpio’s Mr Dovey.

But the reality is that the power of brand is crucial during the selection process. “This does not mean clients will only accept big brands. Small brands can also be successful,” he adds. “But the key is that for clients, recognition of the entity in which they are investing – particularly one that they might not know how to access on their own – is influential.”

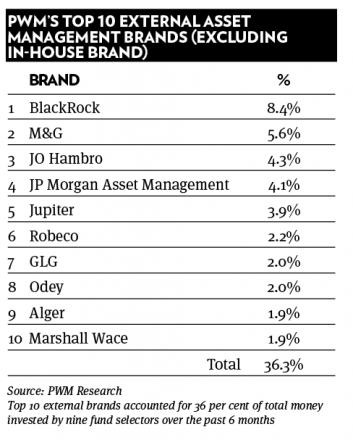

Currently, according to PWM research collating distributor choices over the first half of 2015, five fund groups – BlackRock, M&G, JO Hambro, JP Morgan and Jupiter – are dominating European fund flows.

Continental regulations will boost the trend further in this direction, believes Diana Mackay, whose own list of leading brands contains Fidelity and Franklin Templeton, alongside BlackRock, JP Morgan and M&G. But there is always room for new players, with France’s Natixis rising through her ranks and Credit Suisse set to make a shock comeback, now that Swiss banks are keen to concentrate on more profitable avenues of asset and wealth management rather than investment banking.

Increased communication between these popular franchises and their growing army of fans is helping cement their positions. “Pre-2007, financial advisers said to asset managers: ‘You stay away from our clients; we are the intermediary and the main point of contact.’ But since the financial crisis they have been saying: ‘You need to help us bring the investor back to the market and be our partners in delivering our message.’ In this context, brand has become much more important,” confirms Ms Mackay.

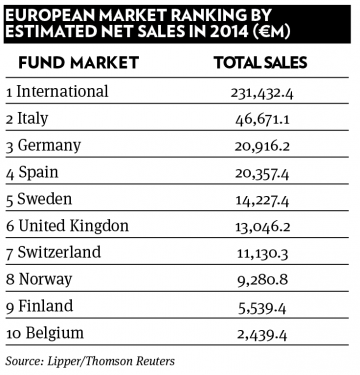

During 2015, European banks have become increasingly confident in selling funds – mainly their own label products – to captive customers, particularly in Italy, Spain and Germany.

“There is a huge pool of investors who have been sitting on deposits. Now they are moving into funds,” she says, with mass affluent customers flocking to high street institutions for new products.

“The consumer rush is coming in through the banks. Wealthy individuals, the mainstay of the cross-border players, are starting to stall further investments, once they see the market is toppy and volatile.”

A surge of money into the fund and wealth management industries is coming from investors not familiar with the market, favouring the biggest brands, she says. “These are not sophisticated investors and they are looking for the comfort of a brand, which helps distributors too sell.”

Boutique players, who have relationships with savvier, wealthier clients are also enjoying good flows, though this is overshadowed by assets being grabbed by the banks. “There is a lot of money moving around and a lot of beneficiaries,” says Ms Mackay.

VALUE FOR MONEY?

But big fund houses are being selected by most private banks as default investment options, believes Mercer’s Cara Williams, with cost leading their criteria. “You identify five fund houses you like and then you use all their funds. That is the most common model,” she says.

“The question is whether you are getting the best in terms of performance. There is no doubt that you are getting the best in terms of fees.”

Most mid-sized private banks are burdened by small, poorly-resourced investment teams, suggests Ms Williams, preferring to manage a small number of relationships with partners they feel comfortable with.

Investment staffs are getting smaller and margins tighter, further boosting the trend of European private banks to direct most flows to a handful of external managers.

“Wealth firms have to maintain margin and there is no better way to do this than decrease number of staff and decrease exposure to numbers of asset management houses,” she adds, believing clients might miss out on up-and-coming firms with newer strategies.

“We want to find smaller, new names out there, especially in less efficient markets,” says Ms Williams. “Big firms have great products, but they are not the best at everything,” with a huge divergence in quality between major names.

“BlackRock puts a lot of emphasis into different strategies run independently, so you are getting the best in class people to run your strategies,” says Ms Williams. “But are all chosen products best in class and would each firm be selected on its own merits in each asset class?”

The concept of a handful of concentrated relationships represents a “very European model” contrasted to the US, where there are “far too many relationships and not enough good products,” says Ms Williams. “Everyone is focusing on managers and houses and not on products themselves.”

But for many private banks, fostering a small number of intense relationships appears to offer some comfort, after they have dipped their toes into the more complex currents of open architecture fund selection.

37%

Although many believe wealth management to be highly fragmented the opposite is true – 37 per cent of the $20.6tn private banks have in AuM is held by the five largest operators, according to Scorpio

Limited resources offer challenges to wealth managers selecting active funds, believes CCLA’s Mr Bevan, especially when it comes to determining persistence of returns and evaluating capacity issues.

Many fund houses fail to transform appealing investment processes into regular returns, often handicapped by fees. “A limited number of relationships can provide the purchaser with more leverage on costs, charges and scale,” says Mr Bevan.

The notion of some giant robotic beasts of distribution, bestriding a crater-pocked surface to mate with a similarly small number of equally hungry fund houses, is one that is likely to remain with us for many years to come.

Once-in-a-lifetime opportunity

Asset managers and private banks need to quickly position themselves to exploit the new appetite for actively managed assets, according to Borja Largo, director of global partnerships at cross-border fund platform Allfunds Bank, speaking at the Fund Forum in Monaco during the summer.

“There is a space now for reasonably priced active managers,” believes Mr Largo. “Our research team is getting many calls about finding the right price for the value which funds are creating.”

This “middle ground” between the large active and passive managers is currently the sweet spot, presenting a “once-in-a-lifetime opportunity” for attracting substantial client assets.

Appetite for alternatives

Successful private banks must provide a much greater range of assets to clients, particularly in the alternatives space, against the backdrop of a low-yielding fixed income environment, claims Luca Paolini, chief strategist at Pictet’s asset management division in Geneva.

“Our favourite asset class is currently real estate, which is less affected by regulation” than private equity and hedge funds, says Mr Paolini. “Contrary to headline news, there is a lot of interest in hedge funds. Although there are not clear trends, there is high volatility and hedge funds should do well in this environment.”

Banks will have a major problem bulking up to meet demand in this sphere, warns CCLA’s Mr Bevan, responsible for launching wealth management at Barclays in the 1980s. “Whereas global bond markets are large and generally liquid, alternatives markets are smaller, less scalable and less replaceable.

“This makes the challenge of building a large business with smaller solutions for underlying clients very tricky and realistically makes the ‘sweet spot’ for asset management much smaller in terms of scale of assets under management than was previously the case.”

He goes on to issue a stark warning to ambitious wealth managers: “The evolution of banks is littered with failed promises and expansion into new markets has often proved more challenging than executive management might have realised.”