Silicon Valley extends deep into US wealth management

Tracey Warson, Citi Private Bank

New York may be the centre of the financial industry in the US, but regional variations mean the biggest banks need a physical presence across the country to cater to clients, as well as overseas if they have global ambitions

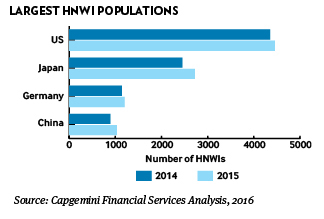

North American wealth growth slowed significantly in 2015, dragged back by underperformance of US companies, according to Capgemini’s World Wealth Report.

While the United States has a special place among financial markets, with the country’s banks still seen as innovative institutions, there is a touch of post-crisis humility creeping into the mentality of its bankers, once keen to roll out their domestically-tested wealth management products across European and Latin American territories.

Leading players such as Citi, JP Morgan and Northern Trust have the benefit of using their US home market as a vast laboratory for the incubation of financial products and services, before these are further tweaked and modified for foreign distribution. But there is a growing realisation that, as with geopolitics, the financial world is no longer a unipolar one.

“The US is very lucky to have Silicon Valley, which is a fantastically entrepreneurial place and one of the most innovative locations in the world,” says Peter Charrington, global CEO of Citi Private Bank, speaking from his Lexington Avenue headquarters, close to New York’s Central Park.

“But you can’t run everything from the corner of 53rd and Lexington if you’re going to be a global bank,” with Citi increasingly deploying ideas developed in its Innovation Centres in Singapore, Israel and India.

Despite these observations, Mr Charrington, an Englishman who has learned to call football “soccer” and embrace the “terrific games” of ice hockey and basketball, both sponsored by the bank, still chooses to be based in the US. It is from this base that he has helped introduce the InView digital project, transforming the previously staid private bank in recent years.

“The digital channel is becoming more and more important to our clients, who increasingly demand the ability to access information on a digital platform,” says Mr Charrington. “But we still need world class people to interpret the data. We don’t expect private banking at the top end to become robo-advisory.”

In the US, Citi tries to keep its ratio of clients down to 30 families, each with a net worth of $25m or above, per banker, says Tracey Warson, head of North America at Citi Private Bank, responsible for managing regional teams across 25 cities in the US and Canada.

“We have a definite aim to keep each banker’s number of clients small, and there’s a good reason for this,” says Ms Warson. “The more wealth a family has, the more complex are the needs we have to handle,” she says.

A native of San Francisco, who until recently lived in Silicon Valley, Ms Warson is also convinced that the tech-led Californian boutique banks springing up will not offer any real competition to the likes of Citi.

While the West Coast is the leading innovation centre globally for technology and “a very special place”, due to its start-up culture, with entrepreneurs willing to take risks, in terms of banks there is only Wells Fargo left there. In the 1980s, there were six or seven banks headquartered on the West Coast, which is no longer a financial centre, having slipped way behind New York.

The new breed of banks, she feels, is trying to feed lower down the food chain. “Firms like Betterment and other robo-advisers are targeted at the retail market. Wealthy families want to be with well capitalised institutions of long standing, for safety of assets. People still want to deal with people and they want relationships.”

The notion of regional teams in the US is better developed than most other jurisdictions, because it is such a large territory, and the market is so mature. This model means adapting to local norms and cultures in vastly differing states and cities.

“To be in Miami for the last 50 years, it’s been essential to have a compliment of staff fluent in Spanish and accustomed to clients’ jurisdictional goals of being in the US and South and Central America,” says Henry Johnson, vice chairman of eastern region business at Northern Trust Wealth Management.

“Wealth management can be distilled into education and stress reduction, which means gaining trust and confidence of our partners. Trust is most easily conveyed in your mother tongue, regardless of how multi-lingual you are.”

Whereas clients in other cities tend to be from older, more established families, New York is home to many more fast-moving, first generation, private equity and hedge fund professionals, requiring a “slightly different approach” from private bankers, suggests Mr Johnson.

These regional variations and dispersion of wealth creation hubs mean having physical teams in place across key wealth centres such as Chicago, Dallas, San Francisco, Miami and Boston, says Citi’s Ms Warson. “Clients like having their bankers nearby, although our local teams are supplemented by experts in New York, particularly for real estate.”

One of the reasons why Citi, and its competitors, appear to have put a slight brake on digital development, is the rising cost of running both a physical and parallel, high-tech digital operation.

“Some of the Swiss guys moved to Santa Monica and stopped wearing ties and watches,” says a headhunter active in both US and European private banking markets.

“But there is a mismatch on the digital side. Banks are frightened by the huge investments they need to make to secure real talent. The real geeks are telling us they want a piece of the action, not to move to a private banking brand.”

This austerity-leaning trend is highlighted by Citi’s Mr Charrington, who has instituted a renewed focus on cost management, which often involves moving non-core staff away from prime real estate locations.

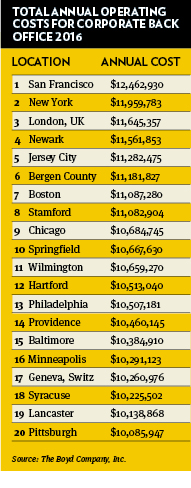

“We are always looking to optimise the right locations from which to serve clients from a cost perspective,” says Mr Charrington, whose bank keeps more than 100 mortgage, tech and operations staff across the East River in Long Island City, Queens, one of New York’s increasing number of outsourcing hubs. Jersey City, a cheaper and less glamorous outsourcing location than the midtown streets of New York, preferred by some rival banks, is also just a ferry ride away.

“Our industry needs to be very focused on cost-income ratios; if they’re not, a lot of players won’t be able to operate any more,” he says. “A lot of cost-income ratios do not make sense, as the banks have lost focus.”

Among the focused services his teams increasingly provide to Citi’s ultra high net worth client base are alternative assets, especially in the form of club deals and co-investments. “There is specific appetite for private equity, strongly supported by today’s economic environment,” says Mr Charrington. North American real estate in New York, Florida and Western cities including San Francisco, Los Angeles, Seattle and Vancouver is also incredibly popular, against the low interest rate backdrop.

Like the clients they serve, many US institutions prefer to have a New York base. While State Street keeps its custody and data operations in Boston, Massachusetts, an hour’s flight away, its flagship SPDR exchange traded funds (ETF) business is headquartered on Avenue of the Americas, at the heart of Uptown New York City, close to the wealth managers the bank is courting.

“Fixed income ETFs represent less than 1 per cent of bond assets and we expect a significant growth opportunity in this product suite,” confirms Tim Coyne, head of institutional sales for SPDR ETFs, who is still feeling “very bullish” about potential uptake of these increasingly popular financial instruments, particularly on the bond side. “In wealth management, ETFs provide cost-efficient solutions for advisers and a great fiduciary tool. From a regulatory point of view, the trend is playing into our hands, anticipating a fee-based model.

“We are entering a democratisation phase for ETFs, opening up asset classes for individuals and intermediaries who did not previously have access to them.”

But there are also dissenting voices in New York’s vibrant financial industry prepared to throw a spanner in the works of all these claims to innovation.

“The problem with private banks is that they have too many masters, such as IT and human resources departments,” suggests April Rudin, a New Jersey-based wealth management marketing specialist.

“For most of these banks, it’s harder to work in-house than out of house. Private wealth is competing for dollars and resources with investment banking and it’s impossible to be first to market, let alone right for market. There are antibodies in all these organisations, which stifle innovation and seek the status quo.”

The next generation of wealthy clients trusts online operators such as Google and Amazon far more than established banks, she believes. “They would rather be with a brand that has been there five minutes than 500 years.”

Asian banks are an exception to the US and European norms, says Ms Rudin. “Asian banks model themselves after Silicon Valley companies. They have core businesses and anything non-core is outsourced. That is why they are able to grow and digitise in a way that US banks cannot.”

Most US wealth managers have made their money by distributing products for external manufacturers, a role which fundamentally conflicts with providing investment advice, says Michael Zeuner, managing partner at WE Family Offices. “Advisers should only be paid by the client to help source the right products. We need to cut out the distribution, which is the most conflicted arena.”

Many US clients have therefore began to use the services of family offices to help them select strategies independently and to give them a better price for products.

“We can come in and get our clients access to investment opportunities, lending and wholesale custody,” says Mr Zeuner. “Private banks are not treating us as somebody they sell to but as a buyer, with an institutional relationship.”

His firm built proprietary technology tools 15 years ago, allowing them to aggregate assets held by clients across a variety of banking relationships.

“We don’t typically see private banks adopting this type of technology,” says Mr Zeuner. “Private banks have done just enough to show clients the big picture, to give themselves a better shot a gathering assets.”

The future of the wealth management industry, he believes, will be forged with the help of technology providers looking to build client-focused systems, rather than the firm-focused platforms of today. The technology exists, he says, to construct “powerful tools” using analytics to both deconstruct a complex portfolio into its constituent parts and to break down every cost associated with it.

“I can see Silicon Valley influencing wealth management, as there is a real role for disruptors, using technology to really change the dynamics of the industry, to help investors cut through the clutter of sales pitches, choose the right options and pay lower fees.”

For Northern Trust, the future lies in further developing its Goal Powered Solutions system, using technology to predict investment solutions for particular goals, such as leaving money to children, donating to philanthropic causes and buying cars or property.

“Typically the industry concentrates on decisions such as whether to add a third small cap manager, to maximise a client’s market exposure,” says Northern Trust’s Mr Johnson.

“We are trying to change the conversation from a dialogue dictated by the industry to make it reasonate with our clients. GPS technology helps us do this. But this is advice-based technology, needing people to explain the nuances of the changing landscape, not the semblance of self-service provided by robo-advisers.”