Radical change for factors shaping emerging market growth

Michael O'Sullivan, Credit Suisse

Fears over falling growth rates and the end of QE have made investors wary of emerging markets, but these economies should receive a boost as the developed world recovers

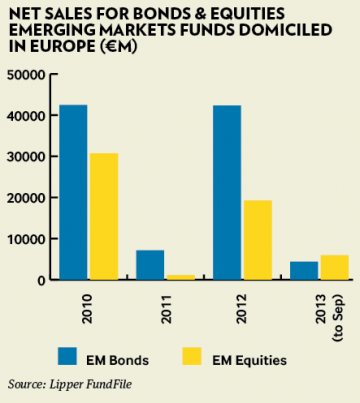

Lower than expected growth rates in emerging market (EM) economies and fears that a reduction of liquidity in the system could generate a new sell-off of EM assets and local currency debt in particular, as in May, when the Fed hinted to tapering quantitative easing and EM currencies significantly depreciated, have weighed heavily on investor sentiment this year.

Investors are shunning EM assets and overwhelmingly prefer developed market (DM) equities and high yield over EM debt, according to the latest BofA Merrill Lynch global research.

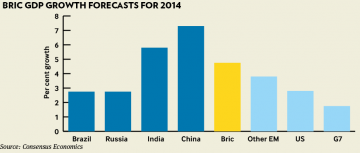

But after the Fed delayed tapering in September and the most affected countries implemented some adjustment measures, the outlook seems brighter for 2014. Private banks remain wary of emerging markets, with China at the forefront of investors’ interest, although the impact of its reforms will lead to slower growth in the short term.

While the notable divergence between DM and EM equities will continue for the rest of the year, in 2014 the gap should narrow, says Adam Tejpaul, head of investments Asia at JP Morgan Private Bank.

“If DM economies can continue the current recovery momentum, it should spill over to emerging economies through the channel of exports and more clarity about tapering of quantitative easing hopefully can provide a more clear direction for EM equities.”

JP Morgan is still cautious on emerging markets, positioning allocations in a very selective way, with a bias towards emerging Asia, in particular North East Asia.

Chinese equities are cheap compared to their own history and regional peers and the reforms dividends are attractive, says Mr Tejpaul. The announcement of the establishment of the Shanghai Free Trade Zone, while still lacking details, could be a milestone in China’s history, as it will promote some dramatic reforms to the existing financial and service sectors. The Third Plenary Session of the 18th Party Congress further demonstrated certain Chinese leaders’ determination to pursue structural reform, as well as the desire for stable growth, he says. The domestic economy is also improving and the export economy should benefit from a broader global recovery.

Today, more than ever, there are sharp divergences within emerging markets, says Michael O’Sullivan, CIO UK & Eemea at Credit Suisse. “The dispersion in views across the various emerging markets is growing as there is a much clearer distinction between winners and losers,” he states.

Emerging market growth rates used to be driven by the same factors, like the rise of China or urbanisation, but over the past year the level of growth of many economies, with India and Brazil being key examples, has slowed down considerably.

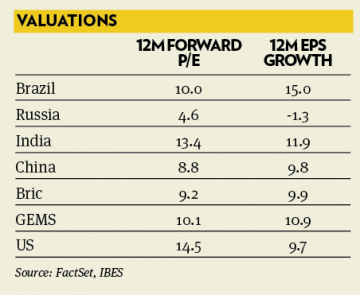

China, on which Credit Suisse is overweight, is quite an exception. “The degree of control the policymakers have on the country seems to be quite formidable,” says Mr O’Sullivan. “The Chinese equity market has had a poor year, it’s been one of the weaker markets, though compared to some of the more developed Asian markets like Korea, the valuation looks quite attractive now.”

Announced reforms could be net negative for its GDP in the short term but over the longer term the volatility in GDP will decrease, he says, as China moves to an entirely different economic model, more based on the consumer, away from government-led investments. “I don’t think any other emerging market, Singapore apart, has got the degree of strategic planning the Chinese are trying to have,” says Mr O’Sullivan.

Russia and Eastern Europe are some of the other EM countries Credit Suisse is overweight. Russian equities have been driven strongly by the oil price and now that the fall in the oil price seems to have ended, stocks are quite cheap and there is scope for a bounceback, says Mr O’Sullivan. Also, Eastern Europe is a good way of playing the European recovery as some of the countries, like Poland, are quite robust.

UBS Wealth Management is overweight equities, in particular the US and eurozone, but neutral on EM equities on a tactical basis, despite acknowledging the long-term forces driving emerging markets growth.

“Earnings momentum has shown some recent signs of improvement in emerging markets, but we want to see confirmation this is sustainable before turning more positive,” says Mark Haefele, global head of investment at UBS Wealth Management. “That said, EM equities are relatively cheap on many valuation metrics, so at this point we also don’t feel an underweight is justified.”

To become more appealing to investors, macro- economic data from emerging markets need to improve, says Pablo Goldberg, global head of EM research at HSBC in New York, and that requires as a necessary condition a better performance from China. “Given the increase in the cost base, you need to see a little bit of improvement on the margins of EM corporates, and part of that will come from weaker currencies,” he says.

The reassessment of risk in the EM space, caused by the change in paradigm by the Fed in May, affected in particular EM economies with weaker fundamentals. Some risks were not probably correctly priced, because there was so much liquidity in the market. But at the same time, this was a “welcome wake up call” for many countries, says Mr Goldberg. This is shown by rate hikes in India and Brazil as well as Indonesia’s higher focus on liquidity of FX markets and its measures to cool down credit creation in domestic economy.

The main investment theme in emerging markets today is about identifying those countries that are better positioned to a combination of higher growth in the developed markets and potential tapering, he says. And also it is about focusing on those economies that are implementing reforms and have managed to keep the cost base in check. Also, countries that have less external borrowing or that are linked to US growth, such as Mexico and Korea, are better positioned.

The speed at which liquidity withdrawal will happen is critical in the evolution of EM currencies. If tapering happens very gradually, which is HSBC’s base case scenario, then there will be a renewed interest for ‘carry’ from asset classes that have become cheaper, such as EM local currency debt.

Talks of monetary tightening in May spooked the market because growth numbers were still very weak, stresses Robert Horrocks, CIO at Matthews Asia.

The Fed’s new chairman, Janet Yellen, is likely to be a much more aggressive advocate than her predecessor of keeping monetary policy loose, until unemployment decreases in the US. When tapering does happen, the global nominal GDP growth will be much higher, being a mixture of real growth and inflation, and typically emerging markets do well in periods of stronger growth, he says. Asia in particular – and the vast majority of the region can fund its own growth, says Mr Horrocks – will benefit, as the US is an export market for many Asian countries. This will also support economies with current account deficits such as India.

Old versus new

The old emerging markets growth model based on cheap labour, exports and foreign direct investments, is dead but the new one is not born yet, points out Gary Greenberg, lead portfolio manager at Hermes Fund Managers.

Today, great opportunities or “gems” are found in these markets in companies that are run in a “highly efficient western model,” which includes environmental, social and governance considerations in the business process. And in the continued war between labour and capital, which the latter is winning, investing in machines and software robotics is the way forward for corporates to become more efficient. “The new model emerging markets have to embrace is about global competitiveness,” he says.

Until 2008, emerging market countries invested, produced, exported and therefore had massive trade surpluses. On the other hand, developed countries leveraged, imported and consumed, therefore having massive trade deficits. “The world is now rebalancing from past successes,” says Samy Chaar, investment strategist at Lombard Odier, “and while the developed world has to change its growth model towards more production, EM countries have to move towards a more domestic demand growth story.”

EM economies are going to have a lower growth rate, but a growth that is leveraged on consumption is more stable than one leveraged on investment.

As the emerging markets’ growth model will evolve, the way of investing in these markets is changing too. The sectors that are linked to domestic demand, not only consumption goods, but also insurance, financials infrastructure or telecoms, look appealing.

Lombard Odier recommends selectivity, stressing investment themes focused on countries, sectors that show some success in shifting their growth model from an investment led to a domestic led bias, and firms that have a sound balance sheet, which are generating cash flow and have a controlled degree of leverage.

In order to succeed, EM economies have to weather interest rate rises – as the rise of cost of capital is going to be detrimental to their rebalancing process – and rising inflation, with Brazil and India the two Bric economies having to face such issues. Losing competitiveness to the Western world, as wages are rising, is a challenge too. Also these economies must show the political will to implement the necessary reforms to favour consumption and reduce savings.

Declining productivity

While many China commentators point to its declining productivity, high wages, debt in the economy, too high a percentage of fixed assets as a percentage of GDP (currently 50 per cent), authoritarian regime, declining growth rates and a nightmare ecology, the most recent plan outlined by the Chinese government, although still very vague, includes very profound reforms, the most profound of which is the rural land reform, says Mr Greenberg.

Giving farmers who move to cities the right to sell their land will unlock tens of trillions of dollars of capital, while farming could consolidate and agriculture become more efficient. More prominent skills could be developed in the cities and wage pressure would be reduced. “Coupled with the reform of the ‘one child’ policy, you would have quite a bit of relief of the productivity problem that China seems to be facing,” he says.

Reforms enabling local municipalities to raise and spend taxes locally, and financing reform will also underline the shift towards an economy where the market role will be “decisive” and “not basic”, according to Chinese government officials.

China, according to Lombard Odier’s Mr Chaar, has the most ambitious plan in emerging markets of rebalancing its economy. After two years of a very fragile economic environment, the country has not devalued its currency and seems on track to achieve its goals. “We would like to see more rapid reforms but if China succeeds, it is going to be very good news for the world economy; if it fails, it is going to be bad.”

Matthews Asia’s Mr Horrocks believes productivity in Asia remains pretty strong. For the past decade productivity growth has been faster than in most of other parts of the world, and wages have gone up in accordance with that. Markets are factoring in the slowdown in productivity and not the fact that the absolute level of productivity is still very high, he says.

He does not agree with the idea that Asia or China have to move to a new growth model or rebalance their economies. Asia’s growth has been based on embracing free market, educating people, saving money to invest in capital goods and being opened to new ideas.

Even when China was growing at 10 per cent, only 2-3 per cent of that growth was represented by exports, and its current account surplus, today close to 2.5 per cent of GDP, is lower than the surplus of 6 per cent in Germany.

In China, household income, which remains steady at 55 per cent of GDP, is expected to rise over time, but the economy cannot be considered out of balance. “Asia doesn’t need to become a more productive society and it doesn’t need to export,” says Mr Horrocks.

High saving rates, openness to new ideas and innovations will drive productivity, which will drive up wages. As wage growth increases, people will change their consumption pattern and habits, which will feed into growth.

Supply side reforms in Asia, and in China in particular, are aiming at increasing the efficiency with which markets allocate capital, and the free trade zone in Shanghai is particularly interesting for the development of a good service and financial sector, he states.

The case for Brics

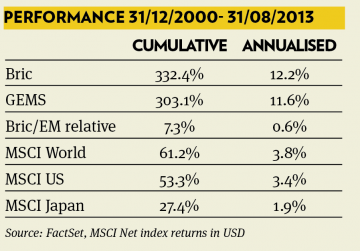

Emerging markets and the Brics have had a disappointing cyclical performance over the past three years, but the longer term structural case is still strong, states Alan Ayres, emerging markets equities product manager at Schroders.

Despite growing much faster than developed countries, emerging markets’ growth rates were as not high as expected after the financial crisis. Growth in developed markets, on the other hand, has beaten expectations. Markets’ reaction to this relative disappointment had a knock on impact on EM earnings, while earnings growth for developed stock markets has been good. Also, whilst there was a squeeze in the profit margins of emerging markets’ corporates, particularly in Asia, and a devaluation on their earnings, corporate profits in the US, as a percentage of GDP, are as high as they were in the 1950s and 1960s on higher valuations.

But large middle class spending, urbanisation, and favourable demographics still support future growth. Investment spending will continue to be strong, although its growth rate will slow relative to consumption, and trade between emerging economies continues to improve.

The share of global GDP is going to continue to shift toward emerging economies and Bric markets, in particular, with their GDP forecast to rise to 38 per cent of global GDP from 20 per cent in 2012. While they are rising, wages are still competitive across Bric markets.

Also, even if improving, debt levels in developed markets are still very high, while in the emerging economies balance sheets are much stronger and debt levels lower.

It is worth bearing in mind that over the longer term the Bric countries have outperformed global emerging markets and the world index and today have fairly attractive P/Es.

Any pick up in global activity will eventually feed through to these stock markets and economies through exports. A lot of bad news is already factored into Brics, and EM stockmarkets, while a lot of good news is factored into developed stockmarkets. Therefore, it is not going to take a lot of good news to see a decent move in emerging markets valuations, which have been depressed, he says.

The main risks for emerging markets are a euro crisis blow-up and the ongoing relative growth disappointment, says Mr Ayres. As many of the EM currencies are still managed against the dollar, a stronger dollar is also a risk. A rise in the dollar would lead to tightening policy in the emerging world – as rates are pushed up to defend domestic currencies – which is bad for their stockmarkets.

Has the Bric acronym had its day?

According to Alan Ayres at Schroders, the underlying principle behind grouping Brazil, Russia, India and China (Bric) together – namely size of population and the ability of these countries to have an impact on the global economy – is still valid today as it was in 2001, when the acronym was coined.

India and China still remain net importers and consumers of commodities, with Brazil and Russia are net exporters and this is not going to change, even if their growth model is evolving.

However, other investment professionals believe size is not the best factor to group countries together today, and while the four countries had a lot in common at an early stage in their growth, their economies have diverged considerably now.

Adam Tejpaul at JP Morgan believes that EM countries could be grouped in a more meaningful way, for example as commodities exporters, such as Brazil and Russia, vs commodities importers such as China; current account deficit countries such as India and Indonesia, vs current account surplus countries, including Korea and Taiwan; countries with comprehensive reform agendas, including China and potentially India, vs countries with little or no reform, such as Indonesia.

However, the creation of the Bric grouping has had the merit of attracting investors’ attention to emerging economies. “It is often forgotten that emerging markets are a very important part of the investment universe as they now contribute well over 50 per cent of global GDP growth,” says Mr Tijpaul.