Look further afield to make fixed income pay

With all eyes on the direction of central banks’ monetary policies, investors continue to be frustrated by government bond yields, though there are attractive returns to be found in other areas of the market

Central banks are gradually gearing themselves up for a change. For the first time since the financial crisis and the resulting waves of ultra-loose monetary policy, it seems as if the major institutions are moving, if not quite in unison, then in spirit, towards tightening.

The US Federal Reserve is leading the way, with rate rises and a reduction in its balance sheet on the cards. The European Central Bank and Bank of Japan are also talking about slowing the pace of purchases, while the Bank of England has hinted at raising rates.

So what does all of this mean for bond markets which have spent the last five years supported by the central banks’ quantitative easing programmes and low interest rates?

Low inflation has fostered a kind of complacency among investors who assume monetary policy easing will go on, believes Didier Saint-Georges, member of the investment committee at Carmignac, whereas in fact normalisation will increasingly become a necessity for central banks around the world.

“This could prove to be disruptive for fixed income investors,” he explains. “A return to normal bond yields — a change Mario Draghi won’t be able to postpone for much longer — is likely to spell trouble for those investors who fail to anticipate the upcoming phase.”

The situation is not quite the same for the Fed though, with the US economic cycle being more advanced. “An outright quantitative tightening could easily be perceived by markets as a reversal of the money creation of the QE period at a time when the economy is about to roll over,” says Mr Saint-Georges. “Such circumstances could well reignite fears of deflationary pressures, thereby dampening the effect on bond yields.”

We may well be approaching a crossroads, but it is extremely difficult to predict what is likely to happen next. Central banks have been enormously impactful in the last five years, in particular with their QE programmes, and with around $15tn of bonds owned by the world’s largest central banks, the real question is what happens when some of that starts to come off the balance sheet?

“You can’t help but feel there is going to be some degree of adjustment as the central banks withdraw their stimulus, but we don’t know how big that will be,” says John Beck, director of fixed income, London, at Franklin Templeton.

Even the central banks themselves seem a little “mystified” as to what might happen, he says, pointing to comments made by Fed chair Janet Yellen as to why inflation remains so low. “When you have one of the world’s largest central banks saying they are not entirely sure what is going on, then there are lots of reasons for other central banks and those who observe them to have a similar degree of uncertainty.”

We are standing on a “slightly dangerous cusp”, believes Mr Beck, with central banks themselves hampered by their own fears of what will happen when they reverse some of this QE. And risk-free bond markets look expensive, he says.

Steady decline

While the financial crisis and subsequent central banks actions have clearly had a role to play in pushing bond yields lower, there is something much more fundamental at play, claims Craig Mackenzie, senior investment strategist at Aberdeen Standard Investments. He points to their steady decline from the 1980s to today. “Back then you got low double digits from government bond yields, and today you are pretty much at zero. That shift has been the defining feature of fixed income markets.”

This has been caused by there being too much desire to save and not enough to invest, an imbalance which is basically pushing down interest rates and bond yields and which Ben Bernanke once referred to as the “savings glut”, says Mr Mackenzie.

There might be talk of normalisation and rising rates, he says, but the overwhelming consensus view is that real interest rates will be very low for the best part of another decade. Those who monitor the bond markets full time might find a shift in yields by 10 or 20 basis points terribly exciting, but to an ordinary investor with a portfolio, it won’t make any difference, he warns.

“And what that means from an investor’s and assets allocator’s point of view is that high grade bonds offer virtually no returns. So I don’t allocate to them at all any more.”

Aberdeen Standard got rid of its gilts entirely three years ago, and has subsequently dumped all of its investment grade credit. It has had a fairly significant high yield exposure over the last 18 months, but that was in a period where high yield spreads went up, but spreads have come down quite a long way since are now at their tightest since the financial crisis.

“Our expected returns for US high yield over the next five years is about 4.5 per cent, so better than gilts, but not a lot of reward for the risk in quite a volatile asset class. We have reduced our high yield exposure significantly and now don’t own any conventional bonds in our multi-asset portfolios.”

Nevertheless, Aberdeen Standard continues to hold something like 40 per cent of its multi-asset strategies in bonds, so where is it investing?

“We still like the asset class and think equities are getting pretty expensive, so we are in fact rotating to fixed income from equities,” says Mr Mackenzie. “We do allocate to fixed income but at the unfamiliar end.”

The firm’s biggest fixed income holding is in emerging market local currency sovereign debt. “The wonderful thing about this is that yields are over 6 per cent and it is a fairly low duration asset,” he says. “So you have a pretty attractive income with relatively low exposure to US interest rate risk.”

Aberdeen Standard also likes asset-backed securities, which provide floating rate yields and which benefit when interest rates rise, a situation which is widely predicted to occur, and is looking to invest in insurance-linked securities such as catastrophe bonds.

QE hangovers

Central banks’ quantitative easing programmes were not only the largest ever direct government intervention in financial markets, but also by far the most distortionary, believes Jan Dehn, head of research at Ashmore. Central banks did not buy bonds pro rata across global fixed income markets, he explains, rather they only bought their own government bonds and asset allocators followed suit, buying into the QE-sponsored markets.

“Who gets the biggest hangovers when the punchbowl is removed? Those who imbibed the most,” warns Mr Dehn. “The QE economies have undertaken almost no reform and investors in these markets should now be asking: with no carry and potential capital losses in store, where are the returns going to come from in the next five years?”

The situation in emerging markets could hardly be more different, he claims. Investors pulled money out of these countries during the QE years, which pushed down asset prices and increased yields, meaning emerging markets now offer both carry and potential capital gains.

“The most profitable trade is likely to be to take profits on the QE markets as a whole and go long on the non-QE markets, which were so out of favour in the last few years. The QE trades are exhausted and crowded. The non-QE markets are uncrowded and far more attractively priced.”

A number of fund managers contacted by PWM see plenty of opportunities in emerging markets, and it seems as if this asset class is becoming a much more strategic holding rather than a tactical play.

Emerging markets used to be a tactical part of investors’ portfolios, but the asset class has gone from nice to have to a must have

“Emerging markets used to be a tactical part of investors’ portfolios,” says Sergio Trigo Paz, head of emerging market fixed income at BlackRock. “But what we have seen is the asset class has gone from nice to have to a must have. It has become core, and now it is about how to gain access rather than whether to be invested.”

But the way in which investors can make money in these markets is changing, he warns. Beta might have made up most of the returns over the last nine months or so, he explains, but this is set to change. “We can expect a transition to alpha. That doesn’t mean beta is going to be negative, but as a percentage of your return, it is going to be less important.”

Historically, the role that traditional fixed income played in portfolios meant that when there was a risk-off shock in markets, rates came down and you made money on your bond holdings, says Eric Stein, co-director of global fixed income at Eaton Vance.

“While that could happen, for example if there was a war with North Korea then US treasuries would rally, the chances are that just sitting around buying bonds in the US or Germany and just hoping for the best is going to leave most investors pretty unsatisfied.”

Rather, being able to go long and short and be able to take advantage of different bond markets and different currency markets is vital in an environment such as the one we are moving into, he believes.

The Boston-based asset manager believes there are opportunities in emerging markets despite the asset class having enjoyed a big rally since its early 2016 lows. “We have seen some sell-offs recently and there is risk, but it remains one of the most attractive areas if you are trying to make money in fixed income,” adds Mr Stein.

There are not much in the way of attractive opportunities in fixed income markets at the moment, says Steven Oh, global head of credit and fixed income at PineBridge Investments, so for investors it is more about looking for the “less unattractive” ones.

“And then it is how do you generate incremental alpha returns? Because if you are buying a little bit of everything to create a global beta portfolio, the net result of that is going to be somewhere between poor and uninspiring. You need to pick and choose your spots and dynamically manage that.”

In order to be able to navigate in this kind of environment you have to be nimble, which is something big asset managers can struggle with, he claims. They might have the ability to identify where to find value, but are so large that they are unable to shift their positions quickly and efficiently enough.

PineBridge currently likes floating rate corporate credit risk in general, which can come in the form of floating rate bank loans and components of structured products. “We also like some emerging markets, but now is not the time to extend your risk profile in high yield EM. Stay in investment grade.”

Still a role to play

So the macro picture may be uncertain, and the asset class expensive while yields are hard to come by, but there is always a role for fixed income in a multi-asset class portfolio, says Anthony Collard, head of investments at JP Morgan Private Bank.

“We are in the eighth year of this bull market cycle, and rates have been extremely low, but actually the asset class has performed extremely well over the last eight years,” he says.

And bonds continue to perform well, he points out, with government bonds posting a positive return despite the low yields, while the spread products, be it emerging market debt or high yield, have enjoyed an “amazing” year.

“You would have missed out on equity like returns if you hadn’t had an allocation to spread products,” cautions Mr Collard.

Nevertheless, JP Morgan is underweight fixed income, because up until now it felt there were better opportunities in equities, alternatives and other asset classes.

Where it is really underweight is government bonds, but it is far from zero. “Equity valuations are extremely high and if and when we get some sort of rotation, we are going to want that duration exposure.”

The private bank says it has reduced duration within its fixed income portfolio in general, even within the spread products, where it favours high yield and emerging market debt.

“We are seeing opportunities though,” says Mr Collard. “When you look at Europe, where there is not a lot of yield, European financials as a sub-sector look interesting. Now is a time where you have to be selective. There are opportunities, you just have to work a lot harder for them.”

Indeed, with equity markets looking expensive and worries over a potential correction, it seems unlikely investors will flee bond markets.

“Diversification is going to be as important as ever so anxiety over rate rises is unlikely to prompt an exodus from bonds altogether,” says Ross Andrews, director of fixed rate bond provider Minerva Lending. “Should investors expect economic pressures to prompt a sell-off in the stockmarket, they may well see bonds as somewhere to weather any storm.”

ETFS start to make inroads

Exchange traded funds have revolutionised the investment world in recent years, but while these vehicles quickly took off the equity markets, their initial uptake in fixed income was much more modest.

Things are starting to change though. “There was a lag between adoption rates of ETFs in equity and fixed income, but we have seen a catch up over the last five years,” says Nicolas Fragneau, head of ETF product specialists at Amundi.

He explains how ETFs can make accessing fixed income markets much easier for investors as it enables them to trade bonds as they would stocks, while it makes gauging the liquidity of a fixed income product much easier.

ETF providers are also adapting the type of fixed income products they are offering. “It isn’t possible to build a full range of products, as you would in the equity space,” he says.

What providers have been doing is trying to find ETFs that are a good fit for investors needs, given the low interest rate environment.

Mr Fragneau explains how Amundi is trying to offer investors things they could not get on their own, such as local currency emerging market debt and floating rate notes.

But plenty of people remain sceptical about the suitability of ETFs to the bond markets. “The problem with ETFs is one of liquidity – they are only as liquid as their underlying market – and systemic risk,” says Didier Saint-Georges, managing director and member of the investment committee at Carmignac.

“A sharp sell-off in high yield, for example, would cause market turmoil as everyone rushes to the same exit door.”

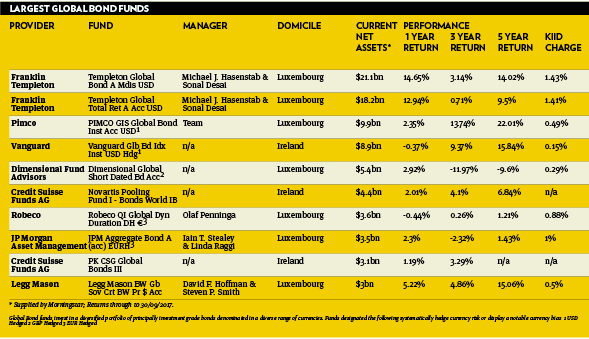

VIEW FROM MORNINGSTAR: A broad menu from which to pick and choose

The global bond peer group offers investors a varied set of strategies. Funds display different risk profiles based on varying combinations of duration, credit and currency exposures. Broadly speaking, Morningstar splits these into two categories: those benchmarked against a broad global government bond index (such as the Citi WGBI) and those with more flexible mandates.

The former are somewhat more benchmark conscious, thus, exhibiting higher duration profiles and lower credit risk than the latter, which look to exploit opportunities in emerging market debt, credit and currencies, along with aggressive duration bets. Most funds, including the largest, sit in the more flexible side.

Year-to-date through September 2017, the average fund in the Global Bond Morningstar category has returned 2.93 per cent (in dollar terms).

Global bond funds have suffered some headwinds over the period. Notably, the rates sell-off in June after Mario Draghi’s hawkish comments at Sintra on “reflationary pressures”, and then again in early September – this time due to expectation of higher inflation and messaging around the Fed’s balance sheet reduction, as well as the ECB rolling back its QE programme. The weakness in the dollar has also weighed on some funds’ performance.

Templeton Global Total Return and Templeton Global Bond, with Morningstar Analyst Ratings of Bronze and Silver respectively, remain the largest funds in this space, despite suffering considerable outflows since hitting peak assets around mid-2013.

Both strategies are co-managed by Michael Hasenstab and Sonal Desai using an identical investment approach. The main difference is that Templeton Global Total Return fund takes on more credit risk than its government-only sibling (Templeton Global Bond). The managers aim to identify value among currencies, sovereign credit, and interest rates, attempting to find those opportunities early on and watch them play out over several years.

The funds have had almost no exposure to the US, the eurozone or Japanese debt, which dominate most peer’s portfolios. They also stand out for their significant bets against the euro and yen. The contrarian-minded group have suffered some periods of underperformance, but over time, long-term-focused investors have been amply rewarded.

Pimco GIS Global Bond, with a Morningstar Analyst Rating of Bronze, has been co-managed by Andrew Balls, Sachin Gupta and Lorenzo Pagani since September 2014. In contrast to Templeton’s positioning, the largest allocations here are typically government debt from the US, the eurozone and Japan.

The strategy allows for considerable flexibility, including investments in corporate and securitised credit and emerging-markets-debt, which the team has historically used to good effect.

Irene Ruiz Espejo, Manager Research Analyst, Morningstar