Bonds to play a different role in portfolios

High quality government bonds may promise safety, but offer extremely low yields. Yet there are still opportunities to be found elsewhere in the fixed income universe

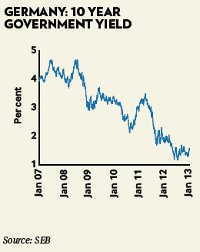

Expansive monetary policies, implemented by central banks to boost the real economy and high investor demand for the perceived safety and liquidity that high quality fixed income assets provide, have driven bond yields down to near historic lows. Depending on maturity, high quality government bonds are generating negative real yields. For example, the 10-year US Treasury bond yields 1.8 to 1.9 per cent and a 10 year German Bund offers 1.6 per cent, both below the rate of inflation in their respective countries.

Investors are actually paying for the privilege to lend money to these governments. “Nominal rates and spreads are now too low to offer a repeat of 2012’s extraordinary gains, when many asset classes in the space enjoyed equity-like returns,” explains Cesar Perez, chief investment strategist Emea at JP Morgan Private Bank. US high yield and emerging markets sovereign debt returned around 15 per cent and 17 per cent in 2012, respectively. “Fixed income investors have to reset their total return expectations for 2013 to still attractive risk-adjusted total returns in the high single digits,” he says.

Key factors to monitor include central banks’ monetary policies, inflationary pressures and capital flows.

Mr Perez expects a gradual slowdown in the pace of purchases from the Federal Reserve from 2014 into 2015, with rate hikes only following a year or two later. This timeline is highly dependent on growth including a recovery in the labour market and inflation, especially since the Fed’s chairman Ben Bernanke has announced formal employment and inflation targets, specifically 6.5 per cent unemployment rate and 2.5 per cent inflation. In Europe, the biggest issue will be growth. Any marked improvement in the periphery growth outlook will be the first indicator for ECB President Mario Draghi to evaluate change in the ECB’s monetary policy, he says. With the election of new prime minister Shinzo Abe, the Bank of Japan has also bowed to political pressure to overcome deflation and revive the economy through quantitative easing, expected to start in January next year.

In the UK, Mark Carney, governor of the Bank of Canada and designated successor of Mervyn King at the Bank of England, suggested that the BoE should ease monetary policy further by abandoning its inflation target, if meaningful growth continues to elude the UK.

It is questionable whether central banks can achieve their growth and inflation targets by pushing financial asset returns, says Emanuele Ravano, managing director at Pimco Europe. The level of debt is already so high and there is a limit to how much it is possible to lever the system. Also, banks today are not an effective transmission mechanism.

Monitoring the market

If monetary policies are not so effective, and the economy is weaker than expected, investors will want to have less risk in their portfolios and stay away from instruments such as high yield, or even equities, and remain in the higher part of the capital structure, ie bonds and safer bonds in particular, he says.

If the positive impact on asset returns – which could be represented by the performance of the S&P 500 – diminishes for a given quantity of bond purchased by the Fed, it means the effectiveness of the monetary policy is diminishing and investors should increase the quality of their portfolio very quickly, says Mr Ravano.

Another indicator is the 10-year US break even level, which indicates expected inflation priced in by inflation-linked assets, he says. US break evens are currently at 2.5 per cent, ie the market expects inflation over the next 10 years to average 2.5 per cent. If they start to rise to 3-3.5 per cent or higher, that would indicate monetary policies have been effective and investors should protect their portfolios against a loss of purchasing power.

“For the moment, inflation does not seem to be an issue in the developed world, as both austerity plans and an output gap of around 3 per cent of potential GDP deflate price pressures,” states JP Morgan’s Mr Perez. Also, money multipliers in the developed world have collapsed as all the printed money is sitting in banks’ balance sheets.

“For inflation to pick up, we would need to see money flowing back into the real economy through credit growth.”

A fear of rising inflation will drive bond yields up and prices down. Downward pressure on prices could also be determined by a significant change in the investor sentiment towards equity investments. This is why it is important to monitor the money flows into fixed income. Indeed, with lower bond yields and improved economic and political fundamentals, the perceived risks in the equity market have diminished, says Giles Keating, global head of research for private banking and wealth management at Credit Suisse. And it would make sense to start moving away from bonds into equities or at least channel new cash into equities rather than bonds, he says.

A rise in interest rates is what worries fixed income investors the most. It may take people off guard, as it might move faster than expected, says George King, head of portfolio strategy at RBC Wealth Management. However, this fear of rising rates should not lead investors to avoid bonds or get out of them, if they have a longer investment horizon. “Rising rates aren’t necessarily as painful as people think for those investors who are looking to generate an investment return and profile over time,” he says.

When yields move up, investors suffer an immediate hit from the price drop, and they typically tend to hold on to their bond holding and get their capital back at maturity.

A more effective approach implemented by active managers is to capture the entire amount invested today and redeploy in the bonds with the higher rates, which enables them to pick up the benefits of the higher rates much sooner.

A new role

Since interest rates have decreased, the role of fixed income has changed greatly, explains Katie Nixon, CIO Wealth Management at Northern Trust. “Bonds are no longer income producing assets because the level of income they generate is so low, but they will still provide that relative diversification and volatility

benefit in their overall portfolio. But it’s important to reset clients’ expectations about the purpose of fixed income in a portfolio,” she says.

Clients should also think about their total portfolio in the context of total return, and not focusing just on income, which leads to a misallocation of the portfolio, says Ms Nixon. Asked about the value of actively managed products in fixed income, she says: “There’s lots of evidence that would suggest there’s little value in active management in fixed income. Research shows the performance of top managers is not significantly higher than the median managers, particularly after fees. But I do think the story’s a little bit more nuanced.” For true passive management to work the index needs to be easily replicable, but in reality it is very difficult to replicate indices, as many are made up of thousands of bonds, the duration of the benchmarks move around and trading in and out of the securities can be very expensive and create a lot of friction and drag, says Ms Nixon.

Investors should therefore keep their eyes wide open when buying passively managed fixed income products and recognise there are some significant benefits to active management, including customisation, which is particularly important in the US with regardsto the municipal bond market, from the tax efficiency perspective. Also active managers can manage across the yield curve, look for relative value, manage credit and durations risks actively.

Opportunities

Although investors have to reset their performance expectations, there are still pockets of opportunities in fixed income. Yields of fixed income securities are at 10 year lows, but credit spreads are at, or near, their historical averages, says JP Morgan’s Mr Perez. “We believe there are still opportunities in extended credit such as high yield, emerging markets (EM) debt, and leveraged loans, given low corporate default rates and robust balance sheets.”

Alternative/non-traditional fixed income strategies, including mortgage backed securities and mezzanine lending also look attractive. European peripheral debt is still the “most unloved” segment in the fixed income space, he says. “We did, however, see value in the short end of the curve at various times throughout the past year, particularly whenever Italian or Spanish bonds sold off too aggressively and the yield curve flattened substantially. On these occasions, we worked together with some of our less risk averse investors, mainly from the periphery themselves, to add back some exposure to their home markets.”

“In this pretty bland, slow growing, low inflation deleveraging world, the best bet is to invest in emerging market bonds,” believes Jan Dehn, co-head of research at emerging markets specialist Ashmore Investment Management. “Any long-term investor who is looking to preserve value and purchasing power for their assets should stay well away from bonds issued by Heavily Indebted Developed (HID) countries,” he explains. This is because their bond prices have been artificially pushed higher by policymakers. But as economies in Europe and US slowly recover and reduce their debt burden, markets will normalise and interest rates will start going up. This will probably happen in 2015/2016 and will lead to other sovereign debt crises as HID countries, such as the US or Spain or Italy, will have to pay higher interest on their debt, says Mr Dehn.

When yields start rising towards their longer term average – 6.5 per cent for 10 year US Treasuries – investors will have to endure a significant per cent capital loss. Liquidity will dry up very quickly and people will not be able to get out of their bond holdings.

On the contrary, EM government bonds are not artificially supported by central banks and generate positive real yields. EM economies have been deleveraging since the mid 1980s and today have low levels of debt and are experiencing strong growth, plus they control 80 per cent of the world’s foreign exchange reserves.

The average yield from a local currency EM bond with roughly five-year duration is 5.6 per cent versus 65/70 basis points of the US fiveyear bond. In addition, local currency EM bonds have a potential currency upside.

EM corporate bonds are the next big wave of capital market development, believes Mr Dehn. “We are seeing a significant growth in the corporate bond universe. We are finally beginning to get financing for the real growth potential in emerging markets, which is locked in private sector investments.”

EM high yield too is attractive as it is trading nearly 600 basis points over 10 year US Treasuries – it traded 270 basis points over before Lehman’s collapse. EM high yield corporates have very good cash generation, very low levels of debt and lower default rates than in other countries, he says. Also, they operate in economies that are growing five times faster than the average growth in HID countries.

But Mark Haefele, head of investment at UBS Wealth Management believes that there is still room for the high yield premium for US high yield bonds to come in this year, despite the spread of US high yield bonds over US Treasuries has decreased significantly: the medium spread in 2012 was about 600 basis points, today it has fallen to about 500 basis points, while the post crisis low was about 450 basis points. Many of the companies that are issuing this debt have much stronger balance sheets than in the past. “Default rates are remarkably low today and investors still have a hunger for yield so that demand for high yield remains very strong. Moreover, many of the new issuances are replacing old debt.”